What to Expect for Vegetable Diseases in 2014

go.ncsu.edu/readext?271031

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲The Vegetable Pathology lab at NC State works in collaboration with the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic to diagnose vegetable diseases and provide disease management recommendations. We have compiled a report to provide our stakeholders with information of some of the trends we observed last year that could help us foresee disease outbreaks for 2014.

Vegetable diseases during 2013

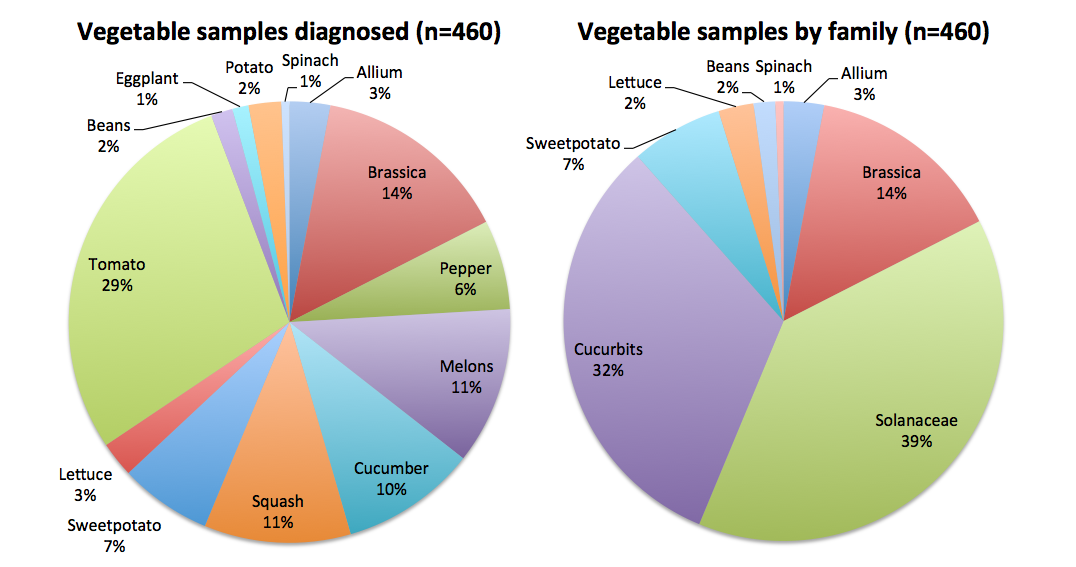

The clinic received approximately 460 vegetable samples last year. Figure 1 shows the percentages of vegetables grouped by type/family, and shows that the majority of samples diagnosed last year were solanaceous (tomato, potato, pepper, eggplant) and cucurbit (melons, squash, cucumber) crops, followed by brassica crops (cabbage, broccoli, collards, turnip, kale), sweet potatoes, allium crops (garlic, onion), lettuce, beans and spinach.

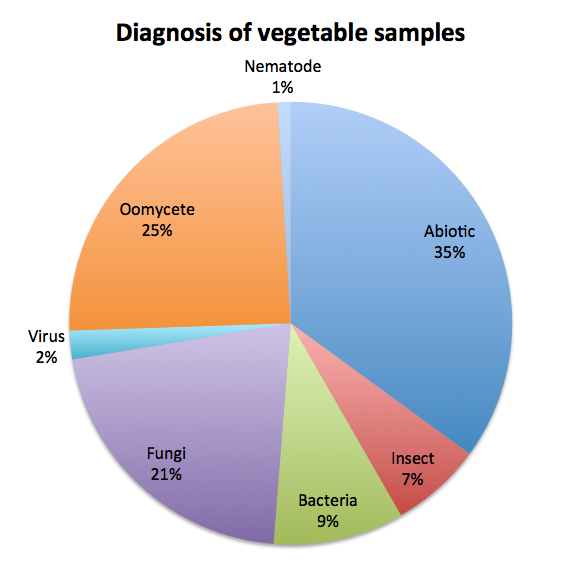

As shown in Figure 2, the majority of samples (58%) were affected by a plant pathogen (oomycete, fungi, bacteria, virus or nematode). When we partition the diagnosis by type, the most frequent diagnosis during 2013 were abiotic causes (fertilization, soils, salts, water stress, injury, chemical burns, etc.), oomycete diseases (in order downy mildew, Phytophthora, and Pythium), and fungal diseases (in order Fusarium, anthracnose, Alternaria, and gummy stem blight). While 65 cucurbit samples infected by an oomycete were diagnosed through our work with the Cucurbit Downy Mildew IPM pipe, even after excluding these samples, downy mildews were the most predominant oomycete diagnosis last year in vegetable crops. However, after excluding these samples, fungal and not oomycete pathogens were the most frequent organisms diagnosed at the clinic as causing diseases last year. We also diagnosed some bacterial diseases such as bacterial leaf spots and fruit blotch, and a few virus and nematode-affected samples. Several samples submitted were affected by insect damage and no pathogens were found.

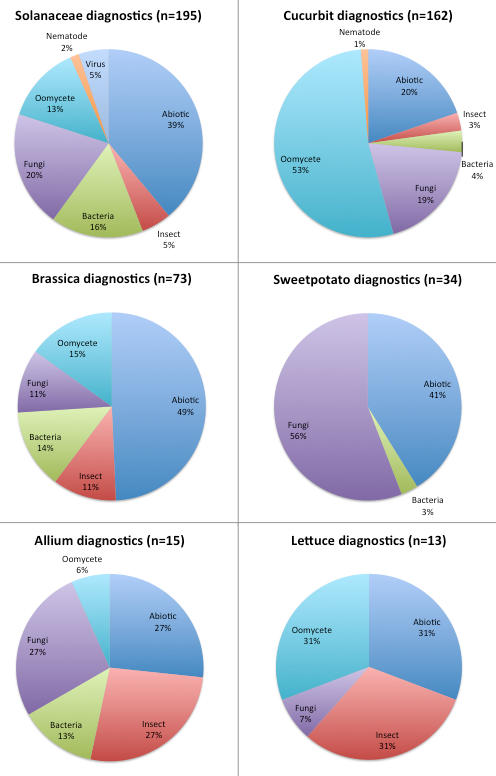

Figure 3 describes in more detail the results for diagnosed samples from the vegetable crops most frequently submitted to the clinic (solanaceae, cucurbits, brassicas, sweetpotatoes, alliums and lettuce). Solanaceous crops were mostly affected by abiotic problems and fungal diseases. In cucurbits, oomycete diseases were the most common cause of crop damage, and if we remove the cucurbit downy mildew samples, fungi and abiotic factors were the main cause of cucurbit disease. For brassica crops abiotic problems and oomycete diseases were the most frequent diagnosis. For sweetpotato more than half of the samples were affected by fungal diseases and others by abiotic causes. For allium and lettuce crops, the most common diagnosis was insect damage and abiotic problems, followed by fungal and oomycete diseases, respectively.

What to expect for 2014

Last year we had a lot of rain, which unfortunately, favored several vegetable diseases throughout the state, and made crop protection and fertilization efforts difficult. For the coming year, we may still face some challenges as a result of last field season. Soil borne pathogen levels may have increased in fields and greenhouses that presented disease last year, the high levels of disease may have facilitated survival of pathogens in weeds and volunteer plants, and flooding may have allowed movement of soil borne pathogens into irrigation water sources or adjacent fields. Thus this coming year, is especially important that you take every precaution to avoid crop losses due to plant pathogens since conditions may be more conducive for disease than in previous years. Here are some things you can do to keep plant pathogens away from your operation:

Use pathogen-free seed and transplants. Try to avoid using seed from previous years to prevent any seed borne diseases, and if you must use seed from previous years consider chemical seed treatments to eliminate any pathogens in your seed. For diseases potentially being introduced into the field through contaminated seed or transplants such as gummy stem blight and black rot of cabbage, is important to start with pathogen-free material, destroy any seedlings showing symptoms of disease and all neighboring seedlings, and protect the seed and transplants with fungicides if possible.

Use appropriate growing practices for your crop. Provide adequate irrigation, fertilization and general growing conditions required for your crop. A vigorous plant will defend itself better from plant pathogens than one that is stressed. Vegetable crops are most susceptible to disease when there is an underlying abiotic stress or injury, thus, having good soil, fertilizing and insect control habits will result in a healthier crop.

Use crop rotation. If you experienced disease problems last year, rotate away from crops that are hosts of the pathogen found in your operation. It is important to accurately identify the affecting pathogen in your operation since it will dictate the appropriate rotational crop, some pathogens such as Pythium and Phytophthora capsici have a very broad host range which can limit the efficacy of crop rotation. A good tool to find out if a fungus or oomycete have been reported to infect a certain host in your state is the USDA ARS Fungal Database. Some growers have also used cover crops, solarization, fumigation, and grafting in cases were inoculum levels of soil borne pathogens are high to successfully reduce disease. You can also consider turning up the soil since most pathogens are found in the first 5-10 inches of soil, however, this will only be helpful for one year.

Use pathogen-free irrigation water. Many pathogens, especially oomycetes, are introduced into fields, greenhouses and hydroponic operations due to use of infested irrigation water. Once pathogens enter your irrigation system, it can be difficult to eliminate them. Take steps to ensure your water sources remain pathogen-free. Many growers use deep well irrigation water, filtration, and UV sterilization systems to ensure water its pathogen-free.

Use resistant varieties when available. Many seed companies carry disease-resistant varieties.

Maintain good sanitation practices. Different pathogens can survive for short or long periods of time on soil, tools, weeds, insects, and volunteer plants depending on the organism. If you know you have an infested field, take precautions to avoid introducing the pathogen into a new field by moving contaminated soil and tools. Diligently control insects and remove weeds, volunteers, and plant debris that can be harboring pathogens. Dispose of any plant debris away from your operation and in a way that will minimize spore escape into the air or irrigation water (you can use a plastic bag, avoid cull piles). In greenhouse and hydroponic operations, try to have little soil exposed by lining your floor with plastic, clean thoroughly with sanitizers benches and any supplies you will re-use from previous growing cycles. In packing houses, make sure you clean packing lines with sanitizers regularly, remove and debris from the line, and ensure antimicrobials in dip tanks are not becoming diluted to the point of being ineffective. If you need to prune your plants use sanitized tools, and avoid handling plants when wet since wounding in the presence of water frequently results in introduction of pathogens into the plant.

Use crop protection. There are several chemical control options for conventional vegetable growers to protect their crops that can be found in the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual. It is important to remember that most products work best as preventive sprays, and that adequate coverage and rates are required for products to be effective. Crop protection compounds usually do not cure a plant disease once its established, they only slow it down in most cases, but they can prevent the pathogen from germinating and growing on the plant if they were applied preventively. Organic growers have more limited options for chemical control, so for them judicious implementation of cultural practices is especially important. Some organic crop protection products are available and they are also most effective when applied preventively. Visit Cornell University’s Integrated pest management website to view guides for vegetable organic operations with information on disease control, you can also consult the OMRI website for specific products.

Make growing conditions unfavorable for disease. Planting early in the season often helps avoid the high pathogen levels that occur well into the summer. Using plastic mulch will help prevent pathogens from reaching leaves and fruit through soil splashing, which are often more susceptible to disease than root and stem tissues. Water management is key for disease control ensuring good drainage, using raised beds and drip irrigation, and promoting air movement will help prevent disease.

Know your enemy. Accurate diagnostics of the pathogen causing problems in your crop is the first step to control disease. The Plant Disease and Insect Clinic can assist you with diagnosing vegetable diseases and providing control recommendations. Once you know which pathogen is affecting your crop, become familiar with the disease by consulting information in the Extension Plant Pathology Portal and talking to your Extension Agent so you can design a disease management plan that works for your operation.

Yearly nationwide epidemics: Cucurbit downy mildew and late blight

For the airborne pathogens that come to the state every year, such as cucurbit downy mildew and late blight of tomato and potato, it is important to use host resistance when available and a preventive spray program since there is little one can do to avoid exposing the crop to the pathogen. When practical, removing infected tissue and disposing of the tissue away from your operation will help reduce local inoculum levels.

It’s important that you keep track of the status of the epidemics by consulting the Cucurbit Downy Mildew IPM pipe website and the USAblight website. Both websites have been established to provide an early alert system to growers so they can initiate preventive sprays once the diseases are found in neighboring states, and they can switch to more aggressive spray programs once the diseases are in the state to avoid any crop loss and unnecessary sprays. To ensure the success of these alert systems it is critical that growers and gardeners are diligent about scouting their crops, and report any confirmed infections to the appropriate website. Because the spores of both pathogens can travel from state to state, controlling these diseases is a community effort. By being engaged in reporting outbreaks and managing these diseases, we can all help protect our vegetable growers. If you suspect you have an infection, contact your local Extension Agent. They can assist you with diagnosis or may help you send a sample to the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic for confirmation if needed. Once an infection is confirmed, your agent can help you report the outbreak to the websites. The reports are done at the county level, and no specific information needs to be provided other than the host crop and the county.

We will continue to publish news and alerts about diseases affecting NC vegetable crops through the Extension Plant Pathology Portal.