How to Control Black Rot of Sweetpotato

go.ncsu.edu/readext?321704

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Written by Andrew Scruggs and Dr. Lina Quesada-Ocampo

Recently, several samples of sweetpotato black rot have been submitted to the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic at NC State University. Black rot of sweetpotato has historically been a very significant disease of sweetpotato in the United States, but it has not been a major problem in more recent years due to the use of better management practices. This year in North Carolina, we have seen an increased number of cases of sweetpotato black rot and have confirmed cases in Johnston, Wilson, Sampson, Columbus, and Nash counties.

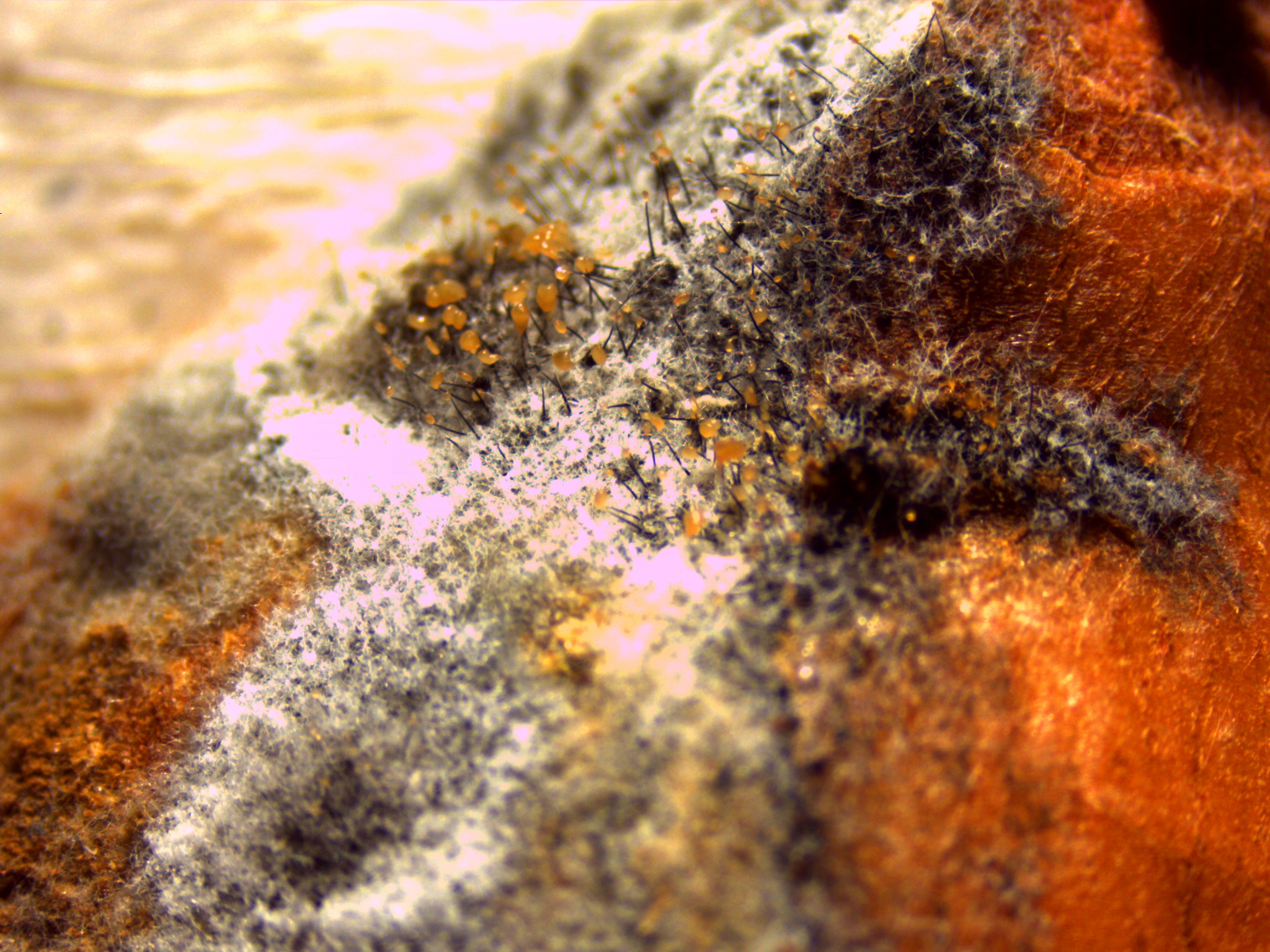

Black rot of sweetpotato is caused by the ascomycete fungus Ceratocystis fimbriata. Symptoms generally appear at harvest or during storage and consist of a dry, firm, dark-colored rot that does not extend into the cortex of the sweetpotato root. Infections typically begin at wounds, lenticels, or lateral roots and can expand in diameter during storage. Examination of infected tissue with a hand lens may reveal the white mycelia and black perithecia of C. fimbriata growing on the lesion surface, which is a key diagnostic feature of black rot. If infected roots are bedded for transplant production, symptoms may also appear on plants in the bed or after planting. Infected slips develop dark, sunken cankers below the soil surface and severe infections can result in the stunting, wilting, and even death of sprouts.

Figure 1. Dark, dry lesion on sweetpotato typical of black rot caused by C. fimbriata (Andrew Scruggs, NCSU Vegetable Pathology Lab)

Figure 2. Black rot typically does not extend past the vascular tissue into the inner cortex of the sweetpotato (Andrew Scruggs, NCSU Vegetable Pathology Lab).

Figure 3. White mycelia and black perithecia as observed at 8x magnification, characteristic of C. fimbriata (Andrew Scruggs, NCSU Vegetable Pathology Lab).

Figure 4. Black perithecia at 25x magnification extending from the surface of a black rot lesion (Andrew Scruggs, NCSU Vegetable Pathology Lab).

Black rot of sweetpotato can be a devastating disease when it occurs, as C. fimbriata produces an abundance of conidia that can contaminate equipment and packing lines, as well as chlamydospores that can survive in the soil for several years. Fortunately, black rot can be effectively prevented and controlled through proper cultural practices. Sweetpotatoes should not be bedded or planted in fields where sweetpotatoes have been grown in the past 3-4 years, fields known to have high incidence of black rot, or in fields infested with morning glories, as these serve as an alternate host. Furthermore, roots selected for transplant production should be disease free and treated with a fungicide such as thiabendazole to kill any fungal structures present on the root surface. Labeled fungicides for sweetpotato can be found in the North Carolina Agricultural Chemicals Manual. It is also imperative that when harvesting transplants, slips are cut at least 2 cm above the soil line to limit contamination of the planting material. Tools should also be cleaned frequently to prevent pathogen spread. Following these preventative steps can significantly reduce the occurrence of black rot during harvest or in storage. Prevention of black rot is imperative as fungicides are not effective against established infections.

While fungicides will be ineffective at controlling rot in already infected roots, steps can be taken to minimize additional losses that could occur during storage. Proper and timely curing of roots at 29°C and 85-90% humidity for 5-10 days will allow for injuries that occurred during harvest to heal and will help prevent secondary infections of black rot during storage. Furthermore, infected roots should be removed prior to washing and packing. C. fimbriata produces numerous spores on infected roots, therefore placing infected roots in a dump tank or onto a packing line will contaminate the packing equipment and significantly increase disease levels. For this reason, it is important to sanitize storage crates and facilities frequently and maintain clean washing machines and packing lines.

Black rot has historically been effectively controlled through the implementation of proper cultural practices and maintaining sanitary harvesting and packing equipment; therefore, by following the control strategies highlighted above, outbreaks of this disease can be limited. If the disease goes undiagnosed and proper sanitation is not practiced, then significant losses can occur. If you suspect incidence of black rot at harvest or during storage contact your local extension agent or submit a sample to the Plant Disease and Insect Clinic at NCSU for proper diagnosis. With this information you can prevent further losses during storage and losses in future years with the proper management practices.

Follow the Vegetable Pathology Lab at NC State on Twitter for more vegetable disease updates.